Work Distribution with Jump Consistent Hashing

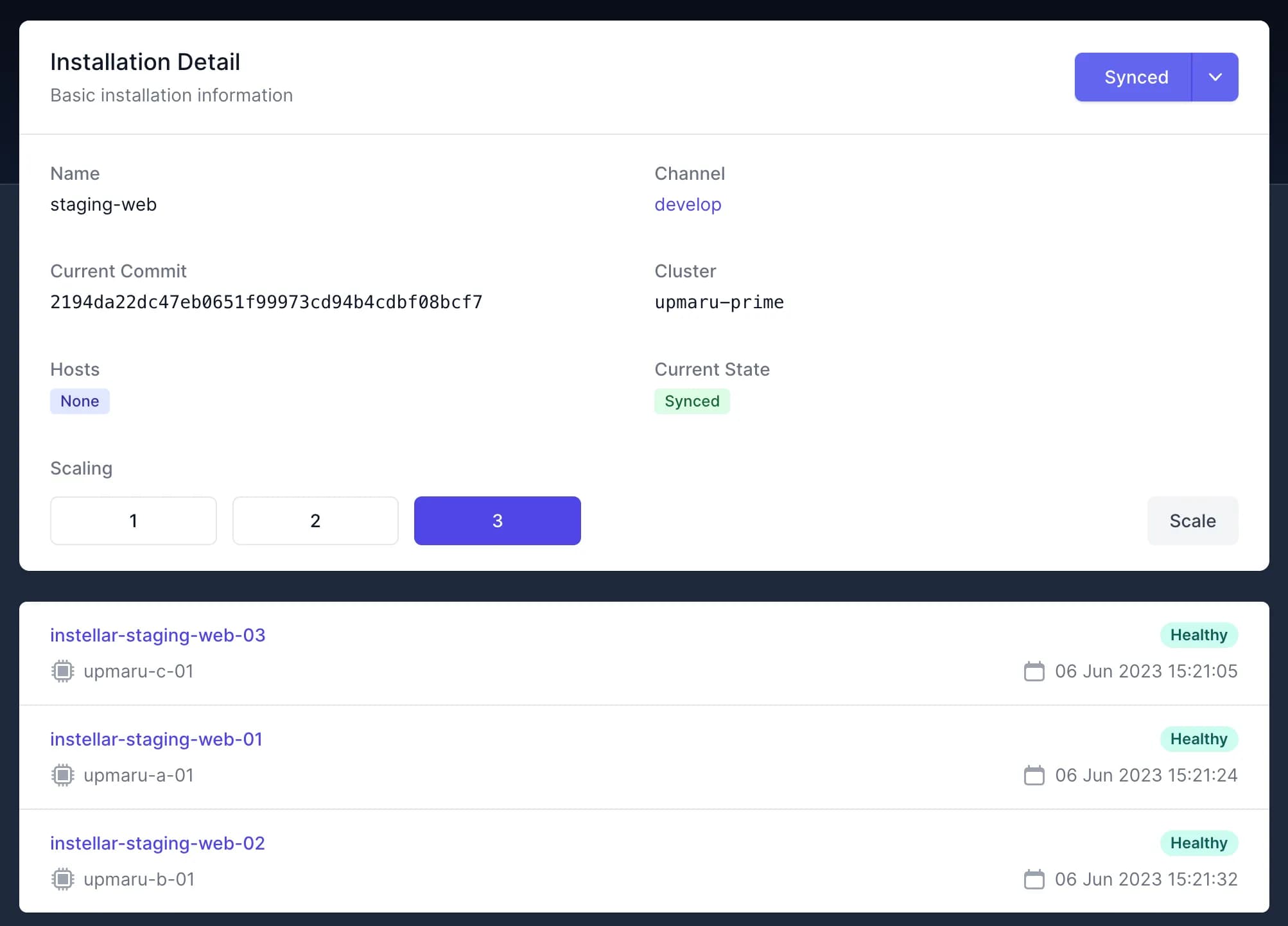

On https://opsmaru.com, we run multiple (3) nodes to ensure high availability. This means we also have compute available on multiple machines. The app is written in elixir, so distributed computing comes naturally. The nodes are aware of each other using :libcluster. So if we run Node.list() we would see a list of nodes like the following. It doesn’t output the node running the command but essentially there are 3 nodes if you include the node running this command.

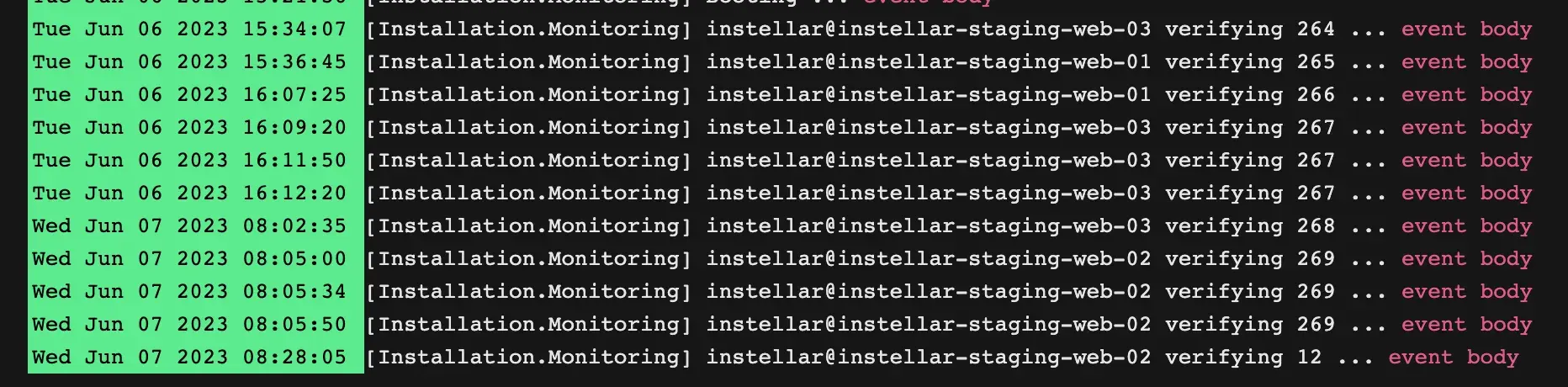

[:"instellar@instellar-staging-web-03", :"instellar@instellar-staging-web-02"]One of the problems that come with distributed computing is how do you ensure a job only runs once. If you use a job queue, the job library will have mechanics to guarantee your job runs once. Throwing everything into a job queue is one way of solving the problem, however given the nature of jobs queue when the job runs is pretty non-deterministic. It’s close to real-time if your job queue is empty, and it can sit and wait in a queue if your system is busy. This can lead to a few problems. Given that this is an elixir based application, coming up with a simple mechanic to ensure updates in the system happen in real-time should be trivial.

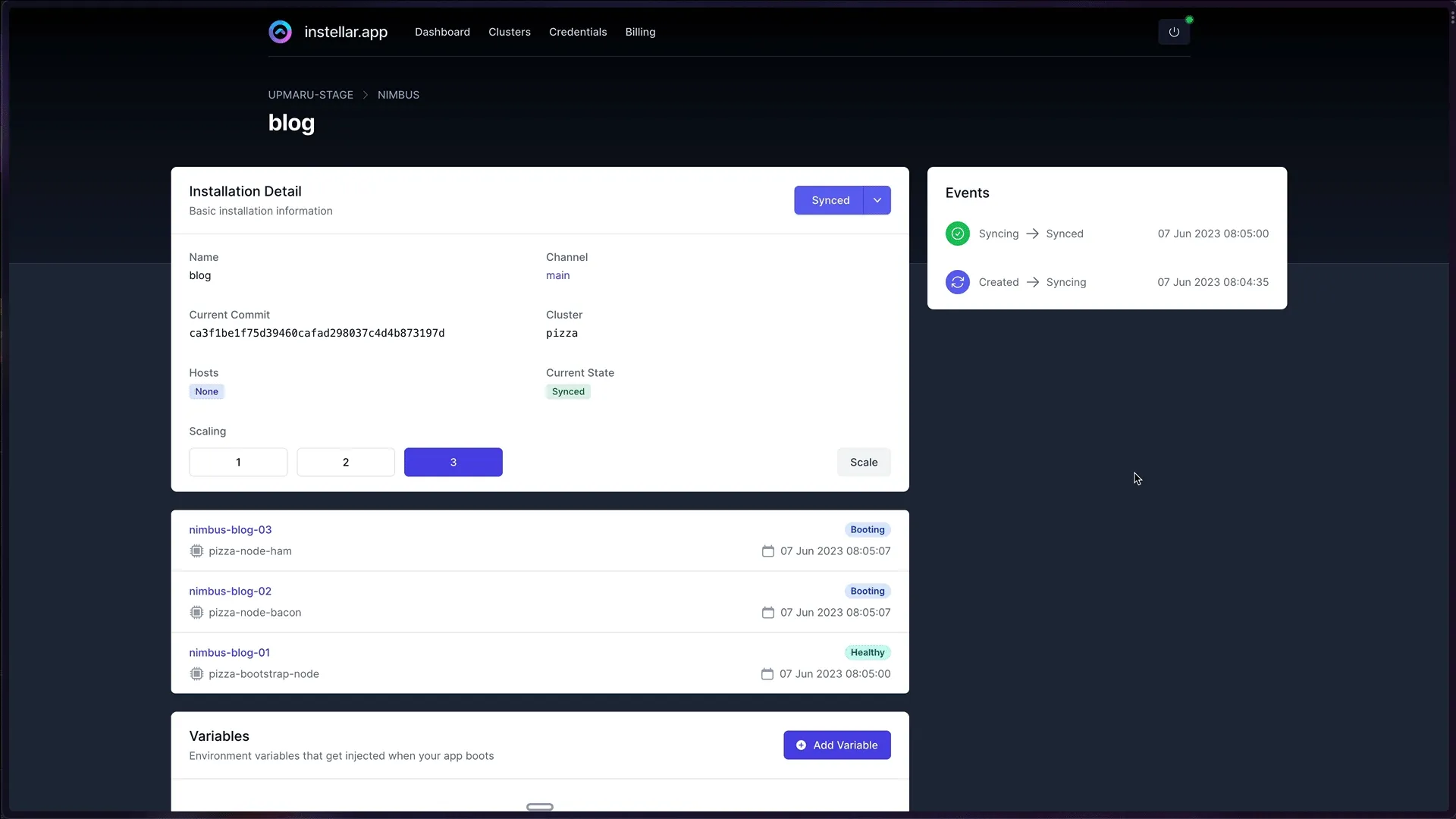

In the example I will use in this article a single resource state depending on the state of multiple resources. In this example the state of the installation depends on the state of the 3 instances running. If the instances are all healthy then the state of the installation should be synced if one of the instances are offline for whatever reason, the installation state should be degraded. If the instances are all offline the installation state should be failing. Now that we’ve set the context. Let’s see how we can solve this problem.

GenServer with PubSub

The app is a phoenix based application, which means we have access to the PubSub mechanism built in to phoenix. Let’s see what happens if we just spin up a GenServer subscribed to a topic.

defmodule Instellar.Deployments.Installation.Monitoring do

use GenServer

alias Instellar.Repo

alias Instellar.Deployments

alias Instellar.Deployments.Installation

alias Instellar.Deployments.Instance

def start_link(opts) do

GenServer.start_link(__MODULE__, opts, name: __MODULE__)

end

@impl true

def init(_opts) do

# normally this would be wrapped in a nice function, but for this blog post

# i'll keep it inline.

Phoenix.PubSub.subscribe(Instellar.PubSub, "monitoring:installations")

{:ok, %{}}

end

@impl true

def handle_info({:verify, %Instance{installation_id: installation_id}}, state) do

# code that will update the state of the

# transition based on the logic explained above

Installation

|> Repo.get(installation_id)

|> Repo.preload([:instances])

|> Deployments.update_installation()

{:noreply, state}

end

def handle_info(_, state) do

{:noreply, state}

end

endThis is a simple setup that should work, however there is a problem with this simple implementation. If we were to deploy this implementation on all 3 nodes it would mean that, when the following code is run:

Phoenix.PubSub.broadcast(Instellar.PubSub, "monitoring:installations", {:verify, instance})The code to verify the installation would run on all 3 nodes. There are many ways to solve this problem, one way is we could just register the Monitoring worker in the global registry by passing name: {:global, __MODULE__} and that would ensure we only had a single worker running on the cluster. But that means we’re not really able to take advantage of our cluster. Ideally we would want to have 3 workers running and be able to split the workload evenly on all of them.

Jump Consistent Hash

Let’s first explore what a jump consistent hash is. Essentially what it does is generates on which of the node a given job should be assigned to. It’s also used in distributed storage, I.E. in a sharded environment which shard in a given cluster should be used to store a given set of data. If you would like to learn more about jump consistent hash, you can read this link. In this case I’ll be using a library called :jumper. We’ll explore some simple example on how we can leverage it in our GenServer.

Mix.install([

{:jumper, "~> 1.0"}

])Jumper is extremely simple. There is a single call, Jumper.slot(1, 3) 1 represents the object id, in our case we can use the installation_id and the 3 is the bucket size. In our case we have 3 nodes. Let’s try running a few examples to see what we get.

iex(4)> Jumper.slot(1, 3)

0

iex(5)> Jumper.slot(2, 3)

0

iex(6)> Jumper.slot(3, 3)

2

iex(7)> Jumper.slot(4, 3)

1

iex(8)> Jumper.slot(3, 3)

2

iex(9)> Jumper.slot(4, 3)

1

iex(10)> Jumper.slot(5, 3)

1

iex(11)> Jumper.slot(6, 3)

2

iex(12)> Jumper.slot(7, 3)

0As you can see it returns the index of the node which we should assign a given task to. For the most part we can also see that it’s evently distributing the workload across the 3 nodes. It’s also worth noting that the same installation_id would go to the same node. So an installation_id of 7 will always be assigned to node 0. This is great if you have stateful workload like downloading a file and processing again at a later time. In our case, our workload is stateless, so this isn’t really an advantage, but having an evenly distributed workload is something we do want.

Our key can also be a string, however we would need to use the :erlang.phash2("something") to first convert it into a hash integer before passing it into jumper.

"something"

|> :erlang.phash2()

|> Jumper.slot(3)Bringing it together

Now we understand what a jump consistent hash is, how do we actually use this in our GenServer. Well imagine we could compute a list of nodes and we could guarantee that the nodes are always in the same order no matter where they’re computed. This means the number output by the jumper could be used to match against which index the node receiving the message is. For example:

cluster = [Node.self() | Node.list()]

index =

cluster

|> Enum.sort()

|> Enum.find_index(fn n -> n == Node.self() end)The code above would basically mean each of the node executing the code would know which index maps to itself inside the cluster. We use Enum.sort() to ensure the list is always the same no matter which node did the computation. Then we match the node on it’s name to find the index

Knowing this we can then match the computed index on each node against the index assigned by :jumper.

This means we can implement a simple logic like below:

if index == Jumper.slot(installation_id, Enum.count(cluster)) do

# execute task to update installation state

else

# do nothing

endNow that we understand that we need to compute a few things let’s introduce the state in our GenServer. Let’s turn our GenServer into a struct.

defstruct [:node_index, :size, :computed_at]

@impl true

def init(_opts) do

# ...

# we now return a struct

{:ok, %__MODULE__{}}

endWe will not compute the state inside the init function because when the nodes boot up, the clustering process may not have happened yet. We will leave that to later so that we can ensure that the state is computed as late as possible to ensure that the node is aware of other node’s existence, given that our solution depends on having the correct cluster size as evident by Enum.count(cluster).

Computing the State

In my solution I compute the state in the handle_info which means when the event is fired. It means I’ll always have the freshest state when the work needs to be done.

@impl true

def handle_info({:verify, %Instance{installation_id: installation_id}}, state) do

state = maybe_compute_state(state)

if state.node_index == Jumper.slot(installation_id, Enum.count(state.size)) do

# execute task to update installation state

{:noreply, state}

else

# do nothing

{:noreply, state}

end

end

defp maybe_compute_state(%__MODULE__{} = state) do

if require_state_computation(state) do

cluster = [Node.self() | Node.list()]

index =

cluster

|> Enum.sort()

|> Enum.find_index(fn n -> n == Node.self() end)

%__MODULE__{

node_index: index,

size: Enum.count(cluster),

computed_at: DateTime.utc_now(),

}

else

state

end

end

defp require_state_computation(%__MODULE__{} = state) do

is_nil(state.computed_at) ||

(!is_nil(state.computed_at) &&

DateTime.diff(DateTime.utc_now(), state.computed_at) > 300)

endI want to have the latest state computed, but I also realize that we do not need to compute the state everytime an event occurs since the cluster size will not change that often. What we’re doing here is we’re storing the timestamp on the :computed_at field and only compute the state if :computed_at is nil or if it’s not nil we check if it has been computed for 5 mins. If it exceeds 5 mins we will recompute the state of the cluster. This logic is computed using require_state_computation

End Result

There are many ways one can solve such a problem, you could use something like :swarm where workers are created on a given event, run the job and then die off. This solution was simple to implement and worked really well and had very few dependencies. Overall I’m quite happy with the way things turned out. I get the real-time feeling of state changes and it looks really cool when you can see it in action in the UI.

You can see from the log output that the work is evenly distributed across 3 nodes.

Thank you for reading! If you need help with your distributed applications, elixir, go, ruby, typescript, nodejs or need help with DevOps / Deployment work, I’m available for consulting. Feel free to reach out to me@zacksiri.dev

Bonus

In the example above I did the work of verifying the installation state right in the GenServer however in reality, there is another way we can make this more scalable. We can wrap the actual work load inside an async Task to achieve some sort of scalability. Since we only have 1 Monitoring worker on each node, it’s smart to use it as a scheduler and delegate the actual work to an async Task. Here is an example how we can achieve this.

def handle_info({:verify, %Instance{installation_id: installation_id}}, state) do

state = maybe_compute_state(state)

if state.node_index == Jumper.slot(installation_id, Enum.count(state.size)) do

Task.Supervisor.async_nolink(Instellar.TaskSupervisor, fn ->

# actual work is done here.

end)

{:noreply, state}

else

# do nothing

{:noreply, state}

end

endWe use Task.Supervisor.async_nolink because should anything bad happen in the task it should not crash our Monitoring server. Since in this case the worker is just a scheduler it should not be impacted if something bad happens in the Task